Aesop's Fables

Aesop's Fables or Aesopica refers to a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and story-teller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 560 BC. His fables are some of the most well known in the world. The fables remain a popular choice for moral education of children today. Many stories included in Aesop's Fables, such as The Fox and the Grapes (from which the idiom "sour grapes" derives), The Tortoise and the Hare, The North Wind and the Sun, The Boy Who Cried Wolf and The Ant and the Grasshopper are well-known throughout the world.

Apollonius of Tyana, a 1st century AD philosopher, is recorded as having said about Aesop:

... like those who dine well off the plainest dishes, he made use of humble incidents to teach great truths, and after serving up a story he adds to it the advice to do a thing or not to do it. Then, too, he was really more attached to truth than the poets are; for the latter do violence to their own stories in order to make them probable; but he by announcing a story which everyone knows not to be true, told the truth by the very fact that he did not claim to be relating real events. (Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana, Book V:14)

Contents |

Origins

According to the Greek historian Herodotus, the fables were written by a slave named Aesop, who lived in Ancient Greece during the 5th century BC. Aesop is also mentioned in several other Ancient Greek works – Aristophanes, in his comedy The Wasps, represented the protagonist Philocleon as having learnt the "absurdities" of Aesop from conversation at banquets; Plato wrote in Phaedo that Socrates whiled away his jail time turning some of Aesop's fables "which he knew" into verses.

Nonetheless, for two main reasons -[1] because

- numerous morals within Aesop's attributed fables contradict each other, and

- ancient accounts of Aesop's life contradict each other,

- the modern view is that Aesop probably did not solely compose all those fables attributed to him, if he even existed at all.[1] Modern scholarship reveals fables and proverbs of "Aesopic" form existing in both ancient Sumer and Akkad, as early as the third millennium BCE.[2] Therefore, at their most ancient roots, the fables of Aesop are composed in a literary format that appears first not in Ancient Greece, Ancient India,, or Ancient Egypt, but in ancient Sumer and Akkad.[2]

Aesop's fables and the Indian Panchatantra share about a dozen tales and there is some debate over whether the Greeks learned these fables from Indian storytellers or the other way, or if the influences were mutual. Ben E. Perry argued for the second possibility in his book Babrius and Phaedrus, making the extreme statement:[3]

- "In the entire Greek tradition there is not, so far as I can see, a single fable that can be said to come either directly or indirectly from an Indian source; but many fables or fable-motifs that first appear in Greek or Near Eastern literature are found later in the Panchatantra and other Indian story-books, including the Buddhist Jatakas".

Translation and transmission

When and how the fables travelled to ancient Greece remains a mystery. Some cannot be dated any earlier than Babrius and Phaedrus, several centuries after Aesop, and yet others even later. The earliest mentioned collection was by Demetrius of Phalerum, an Athenian orator and statesman of the 4th century BCE, who compiled the fables into a set of ten books for the use of orators. A follower of Aristotle, he simply catalogued all the fables that earlier Greek writers had used in isolation as exempla, putting them into prose. At least it was evidence of what was attributed to Aesop by others; but this may have included any ascription to him from the oral tradition in the way of animal fables, fictitious anecdotes, aetiological or satirical myths, possibly even any proverb or joke, that these writers transmitted. It is more a proof of the power of Aesop's name to attract such stories to it than evidence of his actual authorship. In any case, although the work of Demetrius was mentioned frequently for the next twelve centuries, and was considered the official Aesop, no copy now survives.

Present day collections evolved from the later Greek version of Babrius, of which we have an incomplete manuscript of some 160 fabes in choliambic verse. Current opinion is that he lived in the 1st century CE. In the eleventh century appear the fables of 'Syntipas', now thought to be the work of the Greek scholar Michael Andreopulos. These are translations of a Syriac version, itself translated from a much earlier Greek collection and contain some fables unrecorded before. The version of fifty-five fables in choliambic tetrameters by the 9th century Ignatius the Deacon is also worth mentioning for its early inclusion of stories from Oriental sources.[4]

Some light is thrown on the entry of stories from Oriental sources into the Aesopic canon by their appearance in Jewish commentaries on the Talmud and in Midrashic literature from the first century CE. Some thirty fables appear there,[5] of which twelve resemble those that are common to both Greek and Indian sources, six are parallel to those only in Indian sources, and six others in Greek only. Where similar fables exist in Greece, India, and in the Talmud, the Talmudic form approaches more nearly the Indian. Thus, the fable of The Wolf and the Crane is told in India of a lion and another bird. When Joshua ben Hananiah told that fable to the Jews, to prevent their rebelling against Rome and once more putting their heads into the lion's jaws (Gen. R. lxiv.), he shows familiarity with some form derived from India.

The first extensive translation of Aesop into Latin iambic trimeters was done by Phaedrus, a freedman of Caesar Augustus in the 1st century CE, although at least one fable had already been translated by the poet Ennius two centuries before and others are referred to in the work of Horace. The rhetorician Aphthonius of Antioch, wrote a treatise on, and converted into Latin prose, some forty of these fables in 315. This translation is notable as illustrating contemporary usage, both in these and in later times. The rhetoricians and philosophers were accustomed to give the Fables of Aesop as an exercise to their scholars, not only inviting them to discuss the moral of the tale, but also to practice and to perfect themselves thereby in style and rules of grammar by making new versions of their own. A little later the poet Ausonius handed down some of these fables in verse, which Julianus Titianus, a contemporary writer of no great name, translated into prose, and in the early 5th century Avienus put 42 of these fables into Latin elegiacs.

The largest, oldest known and most influential of the prose versions of Phaedrus is that which bears the name of an otherwise unknown fabulist named Romulus. It contains eighty-three fables, is as old as the 10th century and seems to have been based on a still earlier prose version which, under the name of "Aesop," and addressed to one Rufus, may have been made in the Carolingian period or even earlier. The collection became the source from which, during the second half of the Middle Ages, almost all the collections of Latin fables in prose and verse were wholly or partially drawn. A version of the first three books of Romulus in elegiac verse, possibly made in around the 12th century, was one of the most highly influential texts in medieval Europe. Referred to variously (among other titles) as the verse Romulus or elegaic Romulus, it was a common teaching text for Latin and enjoyed a wide popularity well into the Renaissance. Another version of Romulus in Latin elegiacs was made by Alexander Neckam, born at St Albans in 1157.

Interpretive "translations" of the elegaic Romulus were very common in Europe in the Middle Ages. Among the earliest was one in the 11th century by Ademar of Chabannes, which includes some new material. This was followed by a prose collection of parables by the Cistercian monk Odo of Cheriton round about 1200 where the fables (many of which are not Aesopic) are given a strong medieval and clerical tinge. This interpretive tendency, and the inclusion of yet more non-Aesopic material, was to grow as versions in the various European vernaculars began to appear in the following centuries.

Aesop's Fables in other languages

- Ysopet, an adaptation of some of the fables into Old French octosyllabic couplets, was written by Marie de France in the 12th century.[6] The morals with which she closes each fable reflect the feudal situation of her time.

- In the 13th century the Jewish author Berechiah ha-Nakdan wrote Mishlei Shualim, a collection of 103 'Fox Fables' in Hebrew rhymed prose. This included many animal tales passing under the name of Aesop, as well as several more derived from Marie de France and others. Berechiah's work adds a layer of Biblical quotations and allusions to the tales, adapting them as a way to teach Jewish ethics. The first printed edition appeared in Mantua in 1557; an English translation by Moses Hadas, titled Fables of a Jewish Aesop, first appeared in 1967.[7]

- Äsop, an adaptation into Middle German verse of 125 Romulus fables, was written by Gerhard von Minden around 1370.[8]

- Chwedlau Odo ("Odo's Tales") is a 14th century Welsh version of the animal fables in Odo of Cheriton’s Parabolae. Many of these show sympathy for the poor and oppressed, with often sharp criticisms of high-ranking church officials. In commenting on the story of Belling the Cat he notes how criticism of high-handed bishops is not followed by action, 'so in this way the less powerful people allow the more powerful people to exist and dominate them.’

- The Morall Fabillis of Esope the Phrygian was written in Middle Scots iambic pentameters by Robert Henryson (c.1430-1500). In the accepted text it consists of thirteen versions of fables, seven modelled on stories from "Aesop" expanded from the Latin Romulus manuscripts. Among the rest, five of the remaining six feature the European trickster figure of the fox.

- The main impetus behind the translation of large collections of fables attributed to Aesop and translated into European languages came from an early printed publication in Germany. There had been many small selections in various languages during the Middle Ages but the first attempt at an exhaustive edition was made by Heinrich Steinhőwel in his Esopus, published c.1476. This contained both Latin versions and German translations and also included a translation of Rinuccio da Castiglione (or d’Arezzo)'s version from the Greek of a life of Aesop (1448).[9] Some 156 fables appear, collected from Romulus, Avianus and other sources, accompanied by a commentarial preface and moralising conclusion, and 205 woodcuts.[10] Translations or versions based on Steinhöwel's book followed shortly in Italy (1479), France (1480) and England (the Caxton edition of 1484) and were many times reprinted before the turn of the century. The Spanish version of 1489, La vida del Ysopet con sus fabulas hystoriadas was equally successful and often reprinted in both the Old and New World through three centuries.[11]

- Portuguese missionaries arriving in Japan at the end of the 16th century introduced Japan to the fables when a Latin edition was translated into romanized Japanese. The title was Esopo no Fabulas and dates to 1593. This was soon followed by a fuller translation into a three-volume kanazōshi entitled Isoppu Monogatari (伊曾保物語) sometime between 1596 and 1624.

- The first translation of Aesop's Fables into Chinese was made in 1625. It included thirty-one fables conveyed orally by a Belgian Jesuit missionary to China named Nicolas Trigault and written down by a Chinese academic named Zhang Geng (Chinese: 張賡; pinyin: Zhāng Gēng). Another version published in the mid-19th century was initially very popular until someone realised the fables were anti-authoritiarian and the book was banned. There have been various modern-day translations by Zhou Zuoren and others.

- The French Fables Choisies (1668) of Jean de la Fontaine were inspired by the brevity and simplicity of Aesop's Fables.[12] Although the first six books are heavily dependent on traditional Aesopic material, fables in the next six are more diffuse and of diverse origin.

- Around 1800, the fables were adapted and translated into Russian by the Russian fabulist Ivan Krylov.

Versions in regional languages

The 18th to 19th centuries saw a vast amount of fables in verse being written in all European languages. Regional languages and dialects in the Romance area made use of versions adapted from La Fontaine or the equally popular Jean-Pierre Claris de Florian. One of the earliest publications was the anonymous Fables Causides en Bers Gascouns (Selected fables in the Gascon language, Bayonne, 1776), which contains 106.[13] J. Foucaud's Quelques fables choisies de La Fontaine en patois limousin in the Occitan Limousin dialect followed in 1809.[14]

Versions in Breton were written by Pierre Désiré de Goësbriand (1784–1853) in 1836 and Yves Louis Marie Combeau (1799–1870) between 1836-38. Two translations into Basque followed mid-century: 50 in J-B. Archu's Choix de Fables de La Fontaine, traduites en vers basques (1848) and 150 in Fableac edo aleguiac Lafontenetaric berechiz hartuac (Bayonne, 1852) by Abbé Martin Goyhetche (1791–1859).[15] The turn of Provençal came in 1859 with Li Boutoun de guèto, poésies patoises by Antoine Bigot (1825–97), followed by several other collections of fables in the Nîmes dialect between 1881-91.[16] Alsatian (German) versions of La Fontaine appeared in 1879 after the region was ceded following the Franco-Prussian War.

There were many adaptations of La Fontaine into the dialects of the west of France (Poitevin-Saintongeais). Foremost among these was Recueil de fables et contes en patois saintongeais (1849)[17] by lawyer and linguist Jean-Henri Burgaud des Marets (1806–73). Other adaptors writing about the same time include Pierre-Jacques Luzeau (b.1808), Edouard Lacuve (1828–99) and Marc Marchadier (1830–1898). In the 20th century there have been Marcel Rault (whose pen name is Diocrate), Eugène Charrier, Fr Arsène Garnier, Marcel Douillard[18] and Pierre Brisard.[19]

During the 19th century renaissance of literature in Walloon dialect, several authors adapted versions of the fables to the racy speech (and subject matter) of Liège.[20] They included Charles Duvivier (in 1842); Joseph Lamaye (1845); and the team of Jean-Joseph Dehin (1847, 1851-2) and François Bailleux (1851–67), who between them covered books I-VI.[21] Adaptations into other dialects were made by Charles Letellier (Mons, 1842) and Charles Wérotte (Namur, 1844); much later, Léon Bernus published some hundred imitations of La Fontaine in the dialect of Charleroi (1872);[22] he was followed during the 1880s by Joseph Dufrane, writing in the Borinage dialect under the pen-name Bosquètia. In the 20th century there has been a selection of fifty fables in the Condroz dialect by Joseph Houziaux (1946),[23] to mention only the most prolific in an ongoing surge of adaptation. The motive behind all this activity in both France and Belgium was to assert regional specificity against growing centralism and the encroachment of the language of the capital on what had until then been predominantly monoglot areas.

Caribbean creole also saw a flowering of such adaptations from the middle of the 19th century onwards - initially as part of the colonialist project but later as an assertion of love for and pride in the dialect. A version of La Fontaine's fables in the dialect of Martinique was made by François-Achille Marbot (1817–66) in Les Bambous, Fables de la Fontaine travesties en patois (1846).[24] In neighbouring Guadeloupe original fables were being written by Paul Baudot (1801–70) between 1850-60 but these were not collected until posthumously. Some examples of rhymed fables appeared in a grammar of Trinidadian French creole written by John Jacob Thomas (1840–89) that was published in 1869. The start of the new century saw the publication of Georges Sylvain’s Cric? Crac! Fables de la Fontaine racontées par un montagnard haïtien et transcrites en vers créoles (La Fontaine’s fables told by a Haiti highlander and written in creole verse, 1901).[25]

On the South American mainland, Alfred de Saint-Quentin published a selection of fables freely adapted from La Fontaine into Guyanese creole in 1872. This was among a collection of poems and stories (with facing translations) in a book that also included a short history of the territory and an essay on creole grammar.[26] On the other side of the Caribbean, Jules Choppin (1830-1914) was adapting La Fontaine to the Louisiana slave creole at the end of the 19th century. Three of these versions appear in the anthology Creole echoes: the francophone poetry of nineteenth-century Louisiana (University of Illinois, 2004) with dialect translations by Norman Shapiro.[27] All of Choppin's poetry has been published by the Centenary College of Louisiana (Fables et Rêveries, 2004).[28]

Versions in the French creole of the islands in the Indian Ocean began as early as in the Caribbean. Louis Héry (1801-56) emigrated from Brittany to Réunion in 1820. Having become a schoolmaster, he adapted some of La Fontaine's fables into the local dialect in Fables créoles dédiées aux dames de l’île Bourbon (Creole fables for island women). This was published in 1829 and went through three editions.[29] In addition 49 fables of La Fontaine were adapted to the Seychelles dialect around 1900 by Rodolphine Young (1860–1932) but these remained unpublished until 1983.[30] Jean-Louis Robert's recent translation of Babrius into Réunion creole (2007)[31] adds a further motive for such adaptation. Fables began as an expression of the slave culture and their background is in the simplicity of agrarian life. Creole transmits this experience with greater purity than the urban idiom of the slave-owner.

Aesop for children

The first printed version of Aesop's Fables in English was published on March 26, 1484 by William Caxton. Many others, in prose and verse, followed over the centuries. In the 20th century Ben E. Perry edited the Aesopic fables of Babrius and Phaedrus for the Loeb Classical Library and compiled a numbered index by type in 1952.[32] Olivia and Robert Temple's Penguin edition is titled The Complete Fables by Aesop (1998) but in fact many from Babrius, Phaedrus and other major ancient sources have been omitted. More recently, in 2002 a translation by Laura Gibbs titled Aesop's Fables was published by Oxford World's Classics. This book includes 359 and has selections from all the major Greek and Latin sources.

Until the 18th century the fables were largely put to adult use by teachers, preachers, speech-makers and moralists. It was the philosopher John Locke who first seems to have advocated targeting children as a special audience in Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693). Aesop's fables, in his opinion are

- apt to delight and entertain a child. . . yet afford useful reflection to a grown man. And if his memory retain them all his life after, he will not repent to find them there, amongst his manly thoughts and serious business. If his Aesop has pictures in it, it will entertain him much better, and encourage him to read when it carries the increase of knowledge with it For such visible objects children hear talked of in vain, and without any satisfaction, whilst they have no ideas of them; those ideas being not to be had from sounds, but from the things themselves, or their pictures.

In the following century various authors began to develop this new market. The first of such works is Reverend Samuel Croxall's Fables of Aesop and Others, newly done into English with an Application to each Fable. First published in 1722, with engravings by Elisha Kirkall for each fable, it was continuously reprinted into the second half of the 19th century.[33] Another popular collection was John Newbery's Fables in Verse for the Improvement of the Young and the Old, which was to see ten editions after its first publication in 1757. Robert Dodsley's three-volume Select Fables of Esop and other Fabulists is distinguished for two reasons. First that it was printed in Birmingham by John Baskerville in 1761; second that it appealed to children by having the animals speak in character, the Lion in a kingly manner, the Owl with 'pomp of phrase'.

Thomas Bewick's editions from Newcastle on Tyne are equally distinguished for the quality of his woodcuts. The first of those under his name was the Select Fables in Three Parts published in 1784.[34] This was followed in 1818 by The Fables of Aesop and Others. The work is divided into three sections: the first has some of Dodsley's fables prefaced by a short prose moral; the second has 'Fables with Reflections', in which each story is followed by a prose and a verse moral and then a lengthy prose reflection; the third, 'Fables in Verse', includes fables from other sources in poems by several unnamed authors; in these the moral is incorporated into the body of the poem.[35]

In the early 19th century authors turned to writing verse specifically for children and included fables in their output. One of the most popular was the writer of nonsense verse, Richard Scrafton Sharpe (d.1852), whose Old Friends in a New Dress: familiar fables in verse first appeared in 1807 and went through five steadily augmented editions until 1837.[36] Jefferys Taylor's Aesop in Rhyme, with some originals, first published in 1820, was as popular and also went through several editions. The versions are lively but Taylor takes considerable liberties with the story line. Both authors were alive to the over serious nature of the 18th century collections and tried to remedy this. Sharpe in particular discussed the dilemma they presented and recommended a way round it, tilting at the same time at the format in Croxall's fable collection:

- It has been the accustomed method in printing fables to divide the moral from the subject; and children, whose minds are alive to the entertainment of an amusing story, too often turn from one fable to another, rather than peruse the less interesting lines that come under the term “Application”. It is with this conviction that the author of the present selection has endeavoured to interweave the moral with the subject, that the story shall not be obtained without the benefit arising from it; and that amusement and instruction may go hand in hand.

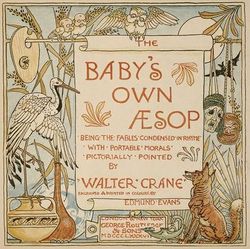

Sharpe was also the originator of the limerick, but his versions of Aesop are in popular song measures and it was not until 1887 that the limerick form was ingeniously applied to the fables. This was in a magnificently hand-produced Arts and Crafts Movement edition, The Baby's Own Aesop: being the fables condensed in rhyme with portable morals pictorially pointed by Walter Crane.[37]

Some later prose editions were particularly notable for their illustrations. Among these was Aesop's fables: a new version, chiefly from original sources (1848) by Thomas James, 'with more than one hunded illustrations designed by John Tenniel'.[38] Tenniel himself did not think highly of his work there and took the opportunity to redraw some in the revised edition of 1884, which also used pictures by Ernest Henry Griset and Harrison Weir.[39] Once the technology was in place for coloured reproductions, illustrations became ever more attractive. Notable early 20th century editions include V.S.Vernon Jones' new translation of the fables accompanied by the pictures of Arthur Rackham (London, 1912)[40] and in the USA Aesop for Children (Chicago, 1919), illustrated by Milo Winter.[41]

The illustrations from Croxall's editions were an early inspiration for other artefacts aimed at children. In the 18th century they appear on tableware from the Chelsea, Wedgwood and Fenton potteries, for example.[42] 19th century examples with a definitely educational aim include the fable series used on the alphabet plates issued in great numbers from the Brownhills Pottery in Staffordshire. Fables were used equally early in the design of tiles to surround the nursery fireplace. The latter were even more popular in the 19th century when there were specially designed series from Mintons[43], Minton-Hollins and Maw & Co. In France too, well-known illustrations of La Fontaine's fables were often used on china.[44]

In the 20th century the fables began to be adapted to animated cartoons, most notably in France and the United States. Cartoonist Paul Terry began his own series, called Aesop's Film Fables in 1921 but by the time this was taken over by Van Beuren Studios in 1928 the story lines had little connection with any fable of Aesop's. In the early 1960s, animator Jay Ward created a TV series of short cartoons called Aesop and Son which were first aired as part of The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show. Actual fables were spoofed to result in a pun based on the original moral. Even more recently there has been a Chinese series for children based on the stories.[45]

List of some fables by Aesop

_-_Foto_G._Dall'Orto_5_ago_2006.jpg)

Aesop's most famous fables include:

- The Ant and the Grasshopper

- The Ass in the Lion's Skin

- The Bear and the Travelers

- The Bell and the Cat (also known as Belling the Cat, The Mice, the Bell, and the Cat, or The Mice in Council)

- The Boy Who Cried Wolf

- The Cat and the Mice

- The Cock and the Jewel

- The Crow and the Pitcher

- The Deer without a Heart

- The Dog and its Reflection

- The Dog and the Wolf

- The Farmer and the Stork

- The Farmer and the Viper

- The Frog and the Ox

- The Frogs Who Desired a King

- The Fox and the Crow

- The Fox and the Goat

- The Fox and the Grapes

- The Fox and the Sick Lion

- The Fox and the Stork

- The Goose that Laid the Golden Eggs

- The Honest Woodcutter

- The Lion and the Mouse

- The Lion's Share

- The Milkmaid and Her Pail

- The Mischievous Dog

- The North Wind and the Sun

- The Tortoise and the Birds

- The Tortoise and the Hare

- The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse

- Venus and the Cat

- The Wolf and the Lamb

- The Wolf and the Crane

- Fables mis-attributed to Aesop include

- The Boy and the Filberts

- The Dog in the Manger

- The Lion, the Bear and the Fox

- The Scorpion and the Frog.

- The Wolf in Sheep's Clothing

See also

- Aesop

- Ancient Greek literature

- Panchatantra

- Uncle Remus

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 D. L. Ashliman, “Introduction,” in George Stade (Consulting Editorial Director), Aesop’s Fables. New York, New York: Barnes & Noble Classics, published by Barnes & Noble Books (2005). Produced and published in conjunction with New York, New York: Fine Creative Media, Inc. Michael J. Fine, President and Publisher. See pp. xiii-xv and xxv-xxvi.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 John F. Priest, "The Dog in the Manger: In Quest of a Fable," in The Classical Journal, Volume 81, No. 1, (October-November, 1985), pp. 49-58.

- ↑ Ben E. Perry, "Introduction", p. xix, in Babrius and Phaedrus (1965)

- ↑ D.L. Ashliman, "Introduction", p. xxii, in Aesop's Fables (2003)

- ↑ There is a comparative list of these on the Jewish Encyclopaedia site [1]

- ↑ The Fables of Marie de France translated by Mary Lou Martin, Birmingham AL, 1979; limited preview to p.51 at Google Books

- ↑ The bulk of the fables can be found on Google Books [2]

- ↑ There is a discussion of this work in French in Épopée animale, fable, fabliau, Paris, 1984, pp.423-432; limited preview at Google Books

- ↑ A reproduction of a much later edition is available at Archive.org

- ↑ Several versions of the woodcuts can be viewed at PBworks.com

- ↑ A translation is available at Google Books

- ↑ Préface aux Fables de La Fontaine

- ↑ Versions of The Ant and the Grasshopper and The Fox and the Grapes are available at Sadipac.com

- ↑ The entire text with the French originals is available as an e-book at Archive.org

- ↑ The sources for this are discussed here: http://lapurdum.revues.org/index916.html?file=1

- ↑ His version of The Ant and the Grasshopper is available at Nimausensis.com

- ↑ The 1859 Paris edition of this with facing French translations is available on Google Books

- ↑ His chapbook of ten fables, Feu de Brandes (Bonfire, Challans, 1950) is available on the dialect site Free.fr

- ↑ A performance of Brisard's La grolle et le renard is available at SHC44.org

- ↑ Anthologie de la littérature wallonne (ed. Maurice Piron), Liège, 1979; limited preview at Google Books Google Books

- ↑ There is a partial preview at Google Books

- ↑ The text of four can be found at Walon.org

- ↑ Lulucom.com

- ↑ The complete text is at BNF.fr

- ↑ Examples of all these can be found in Marie-Christine Hazaël-Massieux: Textes anciens en créole français de la Caraïbe, Paris, 2008, pp259-72. Partial preview at Google Books

- ↑ Available on pp.50-82 at Archive.org

- ↑ They are available on Google Books

- ↑ Centenary.edu

- ↑ Temoignages.re

- ↑ Fables de La Fontaine traduites en créole seychellois, Hamburg, 1983; limited preview at Google Books; there is also a selection at Potomitan.info

- ↑ Potomitan.info

- ↑ See the list at http://mythfolklore.net/aesopica/perry/index.htm

- ↑ The 1835 edition is available on Google Books [3]

- ↑ The 1820 edition of this is available on Google Books [4]

- ↑ Google Books [5]

- ↑ The 1820 3rd edition

- ↑ Children's Library reproduction

- ↑ Google Books [6]

- ↑ See http://mythfolklore.net/aesopica/aesop1884/index.htm

- ↑ http://www.holyebooks.org/authors/aesops/fables/aesops_fables.html

- ↑ http://www.mainlesson.com/display.php?author=winter&book=aesop&story=_contents

- ↑ The Victoria & Albert Museum has many examples: [7]

- ↑ http://www.creighton.edu/aesop/artifacts/tiles/mintonsbluetiles/index.php

- ↑ See several examples at http://www.creighton.edu/aesop/artifacts/tableware/specifickindsoftableware/plates/epinaldepellerin/index.php

- ↑ Aesop's Theater

Sources

- Anthony, Mayvis, 2006. "The Legendary Life and Fables of Aesop". Toronto: Mayant Press.

- Temple, Olivia; Temple, Robert (translators), 1998. Aesop, The Complete Fables, New York: Penguin Classics. (ISBN 0-14-044649-4)

- Perry, Ben E. (editor), 1965. Babrius and Phaedrus, (Loeb Classical Library) Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965. English translations of 143 Greek verse fables by Babrius, 126 Latin verse fables by Phaedrus, 328 Greek fables not extant in Babrius, and 128 Latin fables not extant in Phaedrus (including some medieval materials) for a total of 725 fables.

- Handford, S. A., 1954. Fables of Aesop. New York: Penguin.

- Rev. Thomas James M.A., (Ill. John Tenniel), Aesop's Fables: A New Version, Chiefly from Original Sources, 1848. John Murray. (includes many pictures)

- Bentley, Richard, 1697. Dissertation upon the Epistles of Phalaris... and the Fables of Æsop. London.

- Caxton, William, 1484. The history and fables of Aesop, Westminster. Modern reprint edited by Robert T. Lenaghan (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1967).

Further reading

- Temple, Robert, "Fables, Riddles, and Mysteries of Delphi", Proceedings of 4th Philosophical Meeting on Contemporary Problems, No 4, 1999 (Athens, Greece) In Greek and English.

External links

- Aesopica: Over 600 English fables, plus Caxton's Aesop, Latin and Greek texts, Content Index, and Site Search.

- Children's Library, a site with many reproductions of illustrated English editions of Aesop

- Free audiobook of Aesop's Fables from LibriVox

- Images of Aesopus moralitus - Vita, Fabulae

- Caxton's famous Epilogue to the Fables, dated March 26, 1484